Sparkling Secrets of Dom Pérignon

When Moët et Chandon tour guide Véronique Foureur was baptized as a baby in the Champagne region of France she, like all other Champagnois children, was a given her first few drops of Champagne as part of the ceremony. “You see we all have a lifelong relationship here from birth to death with Champagne,” she says smiling while leading a tour through the Abbey of Hautvillers in France. And nowhere is the ongoing relationship between the region’s namesake sparkling wine and its Catholic faith more on display than in this Abbey where the Benedictine monk Dom Pérignon worked as a cellarmaster in the 17th Century and is laid to rest before the altar. Today, Dom Pérignon’s name is used for the prestige cuvée of the Moët et Chandon Champagne house. The company has helped preserve the Abbey and restored its small vineyard that Dom Pérignon used to oversee more than three hundred years ago.

Perhaps no other Champagne is as iconic a brand with worldwide recognition as Dom Pérignon. From its antique-looking label to the distinctive bottle shape based on 17th Century designs, Dom Pérignon is a symbol of luxury engrained in pop culture. But beyond the hype, Dom Pérignon is also recognized by serious wine critics as a consistently exceptional example of the top tier of Champagnes.

At the center of this consistency over the years is Richard Geoffroy, the Chef de Cave of Dom Pérignon for the last decade. He has the final say on every aspect of the creation of this legendary Champagne from the vineyard to the timing of a vintage’s release.

During a vertical tasting arranged for American wine journalists at the Abbey of Dom Pérignon going back through 40 years of vintages, Geoffroy shared his approach to winemaking and the techniques he uses when crafting sparkling wine.

While many sparkling wine producers look at a grape’s acid and sugar levels as top factors determining age-ability and quality, Geoffroy has a slightly different spin. “To me pH is the most important aspect of the fruit we pick. I think there is too much emphasis among Champagne makers on acidity. In my mind pH is at the top with acidity, flavors and sugars further down the scale of importance. If we need to do any corrections, I prefer we do so through blending.”

Geoffroy is also a big believer in doing what he can to control the end product. As a result they add sulfite during their pressing to kill off any indigenous wild yeast, only use stainless steel tanks for their primary fermentation and prefer to use two different cultured house yeast strains, one for the primary fermentation and one for the secondary fermentation. “With our strains we know how they will perform during fermentation so we can better control the outcome,” he says.

Looking for no surprises later during the winemaking process, he runs a malolactic fermentation with a commercial culture each year and allows it to complete fully. He adds the malolactic culture about one month after starting his primary fermentation.

The art of blending is the true secret to most great sparkling wine. Geoffroy begins tasting his new batches when they are about two months old. He and his team will taste the separately fermented young Chardonnay and Pinot Noir to determine blending percentages. Unlike other Champagne producers, Dom Pérignon does not use any Pinot Meunier in their wines.

“I tend to use roughly a 50% Chardonnay and 50% Pinot Noir blending guideline for Dom Pérignon, although some years it can be 60:40 or 40:60, depending on the needs of the vintage,” he says. “There are three grapes we are allowed to use for Champagne, but blending across the two is what we do here. It is tougher to just rely on the two varieties but I feel the tension between these two grapes can ultimately be more rewarding. The front and middle of tasting Dom Pérignon comes from the Chardonnay while the second part of the middle and finish belong to Pinot Noir.”

With wine critics and customers expecting Dom Pérignon to hold up to decades of aging, the topic of oxidation understandably gets a lot of attention from Geoffroy. “Oxidation kills a Champagne’s complexity and makes it fat and heavy,” he says shaking his head.

He protects his wine against oxidation with a mix of both early exposure and later protection. “We do not baby the must early on before adding the yeast. Oxygen is not a bad thing at the early stage and I think it acclimates the juice later against future oxygen pick-up. At later stages, we gently rack and protect with sulfite at key times such as disgorging,” Geoffroy explains looking into a Champagne flute holding a 1966 vintage.

Dom Pérignon ages on its lees in the bottle for a minimum of seven years before riddling and disgorgement. After the yeast is removed, the Champagne is stored for another six months before being released for sales around the globe. Geoffroy is in charge of determining which year’s wines should be designated as a vintage year since Dom Pérignon is exclusively a vintage Champagne. As a result all of his Champagnes are made from wines produced in the same, single year, unlike many other Champagnes that are non-vintage blends from different years. If a vintage is not up to Geoffroy’s standards no Dom Pérignon will be released for that year. As a rule, it is made no more than six times per decade.

“There is quite a bit of pressure being responsible for this name,” he says heading off to check on some freshly picked grapes. “Every vintage is unique so it is not just mastering techniques to create great Champagne. I have found creativity is one of a winemaker’s best tools.”

Sidebar: The Monk, The Myth

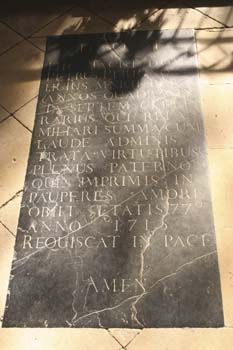

Dom Pérignon was born Pierre Pérignon in 1640 just east of the Champagne region. He joined the Benedictine Order at 19 and was appointed cellarmaster at the Abbey of Hautvillers when he was 28. He remained the cellarmaster until his death in 1715. As cellarmaster, Pérignon was in charge of the abbey’s vineyards and winemaking. The wine he made was used both by the church itself as well as sold to raise money for the abbey.

Pérignon is frequently given credit for inventing Champagne as well as the famous quote, “Come quickly, I am drinking the stars,” when describing his first sips of sparkling wine. However, both are just popular myths.

His classic quote was the work of an advertising agency two hundred years after he died and refermentation in the bottle — as home winemakers are well aware of — can be a problem when dormant yeast comes back to life.

In Pérignon’s day, sparkling wine was more of a fault, not a carefully orchestrated end product. Without the temperature controls we take for granted today, refermentation was a big problem when spring temperatures would creep up, reawakening the yeast from incomplete fermentations resulting from cooling temperatures in the fall. Exploding bottles were dangerously common.

While Pérignon wasn’t the first to make Champagne, he was a true innovator of his day with his winemaking. Rather than just looking at the bubbles in the bottle as a fault, he looked to make this product safer and better.

He was a pioneer in blending, looking to combine different grape varieties from different vineyards rather just relying on the fruit on hand, which was the standard practice of his day. He would evaluate the fruit by taste, purposefully not knowing the vineyard it was sourced from to avoid prejudice. He concentrated on the fruit quality first and how it would work with the other grapes he was going to use. This “blind” tasting method has led to another myth that he actually was blind.

Pérignon also was one of the first winemakers to press red grapes immediately to collect white juice for his winemaking, one of the centerpieces of modern Champagne making.

To make wine safer, he introduced the use of thicker glass bottles to withstand the carbonation created by refermentation and a closure made of hemp rope that was the predecessor to the wire cage used today. He also was one of the first in the region to use stronger corks made in Spain.

For several hundred years, Dom Pérignon’s name has been used by the region’s winemakers to help sell their product. Several small local producers named their Champagnes after the famous monk, hoping to ride his legend to greater sales in the 1800’s. Then, in the 1920’s, Moët et Chandon legally adopted Dom Pérignon’s name for their new prestige cuvée being launched, resulting in worldwide name recognition for this innovative winemaking monk.

Dom Pérignon didn’t “invent” Champagne, but he was at the forefront in his day of better managing and taking advantage of the natural fermentations that make sparkling wine so special.