Amarone-Style Wine Kits

Most wine drinkers who have been exposed to Amarone probably consider it to be another one of Italy’s signature wine styles — perhaps the most brutally powerful and distinctively flavorful, but one of many in a country of strongly idiosyncratic tradition.

It is more than that. Amarone harks back to the beginnings of winemaking. In addition to being a link to a winemaking (and drinking) tradition of the distant past, it has an important position in the progress of technology, qualifying as one of the first wines to have its must strength manipulated to extend its shelf-life.

And, of course, this being a kit column, I can’t resist: Grape winemakers would have an extremely difficult time replicating Amarone for themselves at home. Not only are the three grapes used in it in short supply for most of us, but also trying to replicate the techniques of the ancients is easier contemplated than executed in a modern winemaker’s home. So who’s there to make sure you get your fair-share of Amarone? Why, the noble wine kit of course!

Amarone in history

Original winemaking is so easy that it might simply have been established through accident: Store a jar or bucket full of grapes, and in a few days the juice of the burst berries will have sharpened and become less sweet — and entirely more interesting — even if you do have to drink this primitive beverage through a strainer.

But such wine has drawbacks. Usually made from unpruned wild grapes, it would rarely have reached the sugar levels (°Brix) required for long aging and would have spoiled in just weeks. One of the first recorded clues we have about the steps that ancient peoples took to overcome this sugar deficit is in the Greek epic poem about Odysseus.

Odysseus, you will recall, slipped a mickey to the cyclops, Polyphemus, liquoring up the big squinty giant and poking him in the eye, thus making his escape. For those of us raised on cool old stop-motion animation films for our Mycenaean history, this is as far as we got. But if we read a translation of the text of the Odyssey, we learn that the wine he used was Maronean, a beverage described as “red wine, honey sweet” and so strong that it was only ever drank diluted with water.

For a poor cyclops used to low-alcohol Sicilian plonk, Maronean wine served straight up must have been like a stun-gun to the cerebral cortex, dropping him like a load of mono-browed bricks. Interestingly, the story says he was so peevish upon waking up blind and hung-over that he threw a number of rocks at the retreating Odysseus, which now form an archipelago of tiny islands sticking out of the sea near Mt. Etna.

Part of the strength of Maronean wine could be attributed to better cultivation methods — staking the vines instead of simply allowing them to grow up trees or over arbors, but the real secret behind wine so strong that it can’t be drank undiluted (at least not without consequences) is due to the incredible cleverness of these ancient winemakers — who actually invented the first recorded grape concentrate technology, now known as appasimento. By taking ripe grapes and drying them on straw mats, they were able to increase the sugar content of the resulting musts until they exceeded 16% in potential alcohol — enough to drop an unsuspecting cyclops in his tracks!

Veneto, Ripasso and Amarone — ancient wines, modern times

The modern spiritual inheritor of Odysseus’ Maronean tipple is made in the Veneto region of Italy. If you visualize Italy sticking out like a boot into the Mediterranean, the region of Veneto is up in the northeast, behind the knee, where that little finger-loop goes. It is Italy’s 3rd largest wine producing region, ahead of Tuscany but behind Apulia and Sicily. Its two best known wines are Soave and Valpolicella. Soave’s image is, at best, that of a neutral white wine, consumed in large quantities at ice cold temperatures — which can’t be knocked when the situation calls for such things.

Veneto’s red, Valpolicella, varies enormously in quality. Made from a blend of three grapes, Corvina, Rondinella and Molinara, it is best within 1 or 2 years in the bottle. It can be a fresh, fruity style of wine, but prevailing market conditions in Veneto don’t encourage the production of high-value wines. Half of all the production is in the hands of cooperatives, and another 20% is in the hands of big industrial wineries, both of which normally produce high volumes of cheap wine. This is a recipe for falling wine values and loss of quality.

It doesn’t necessarily have to be this way — in fact, some wonderful Valpolicella Classico can be found in single vineyard wines owned by independent growers, if you know where to look. In addition to this, there are two truly great styles from Veneto using appasimento grapes, Amarone and Ripasso.

Ripasso is a sort of second-run wine, traditionally made by pumping young Valpolicella over unpressed grape skins (i.e. the lees left after the free run wine has been removed) from a full Amarone fermentation. The resulting wine is sweet and rich, and acquires some of the power and complexity that is so distinctive in great Amarone. Rather than recycle Amarone skins, some modern versions use partially dried grapeskins of their own, and produce an equally intense, but slightly fresher, fruitier Ripasso. This would most closely resemble the ancient Maronean wine in strength and sweetness.

The finest wines of Veneto, and the ones that we’re interested in, are the Amarone Della Valpolicella Classico. Traditionally the best bunches of grapes are laid out on mats in a well ventilated room where they are left to dry until the end of January. The conditions during this drying period (the aforementioned apassimento) are important. Without plenty of ventilation and warm dry days, the grapes could develop high concentrations of the Botrytis cineria fungus, which would add unwelcome flavors to the red wine. A bit of Botrytis is expected, and adds complexity and intensity, but too much can overwhelm the wine.

At the end of January, when the grapes have lost up to 30% of their original volume, they are crushed and fermented. Most of the water will have evaporated and the flavor of the grapes is concentrated by the drying process. The fermentation is long and slow, usually taking about four months to complete. Up until the 1950s careful steps were taken to make sure the wines stopped fermenting at about 14% alcohol, retaining rich sweetness and the wine was sold as Recioto Della Valpolicella (“recioto” is derived from the Italian word for “ear,” referring to the selected upper lobes of the grape bunches usually chosen for drying). Recioto is in interesting wine, but is more suited to drinking like a Port, at the end of a meal rather than as a table wine.

Veneto legend has it that an incautious winemaker allowed his barrels to ferment completely dry, resulting in a 16–17% wine of incredible power and intensity. The very word “Amarone” is derived from the Italian amaro, meaning bitter. Good Amarone has a tartness and astringency to it, with a luscious edge of raisiny-sweet black fruit, like a Christmas pudding poured into a glass.

While standard Valpolicella is intended to be drank within a year or two of bottling, Amarone is barrel aged for up to four years before release, and will require another three to five years to come around and lose some of the brooding intensity of its youth, and will then hold its towering peak of flavor for 10 to 15 years — a wine truly intended for the ages.

Amarone from kits: Appasimento in a box?

Wine kit manufacturers are constantly searching for ways to expand their product line-up, looking from cold climate traditionalists like the Germans to hot climate iconoclasts like the Australians. But the source of so much of our wine ideas and traditions harks back to the old country in Italy. It was natural that the major manufacturers would offer an Amarone style to their customers. Not only is it a fabulous wine, it is also a prestigious name, and has broad appeal to consumers looking for a bigger wine experience from their kit.

Generally the kits are the larger, “6-week” style, with approximately 3 gallons (11.4 L) plus of juice-concentrate blend, and come in two formats, with grape material or raisins and without, and two styles, Recioto and Amarone, depending on the sweetness of the final wine. It can be just a little confusing, as some manufacturers make Amarone, Recioto, and Super-Valpolicella styles under proprietary names. With a little luck, and consultation with your local homebrew shop, you should be able to sort out which one you’re looking for (although it wouldn’t hurt to try any one of them!)

It turns out that while taking four months to dry expensive, imported Italian grapes in the dead of winter isn’t really practical for a home user, it’s not only practical for a wine kit, it’s a natural — kits are made with concentrate to begin with, and pre-packaged grape material is commonplace in high-end kits.

Pre-balanced and free of Botrytis and other potential contaminants, as well as being free of oxidized and spoiled grape material, the kits make the more modern style of Amarone, with intensity of fruit, a dry edge, and vastly gripping tannins and body.

Things to watch out for with Amarone kits

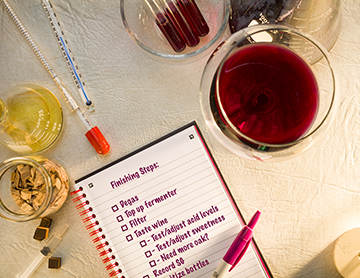

Read the instructions, from beginning to end before starting the kit. Amarone can have a few tricky moves to it, so you don’t want to get halfway through the process and suddenly wonder, “What is this extra bag of stuff for?” Always Read The Instructions!

Starting volumes

Be sure to rehydrate the must to the precise volume indicated in the instructions, usually 6 gallons (23 L). Because Amarone already starts at a very high gravity, leaving out some of the water will bring the sugar content (and thus the osmotic pressure) too high for successful yeast metabolism. Use a primary fermenter of at least 7.9 gallons (30 L) to allow for foaming and a potential cap of grape material.

Watch the pitching temperature of the must. While some wine books advocate cool temperatures to increase retained fruit character in fermentations, they don’t take into account the specific requirements of every kit on the market. Follow the manufacturer’s temperature requirements precisely, and don’t pitch the yeast if the must is too cool or too hot — it can lead to downstream problems with slow fermentations, excess CO2 gas at clearing or stuck fermentations.

If your fermentation room is too cool, it could slow down the yeast and extend both fermentation and clearing times. If it’s too hot, it could lead to malignant hyperthermia, where the temperature of the must climbs on its own, heating up enough to cook off the yeast and cause a permanently stuck fermentation.

If your kit comes with an extra pack of sugar, it needs to be handled precisely. Extra fermentables are included in some kits to increase the alcohol content of the finished wine. However, if they are added in the beginning on day one, the sugar concentration of the must can be too high for the yeast, resulting in stuck fermentations and sweet wine. Follow the instructions closely, and add them when directed, usually 5–7 days after the start of fermentation.

A last piece of advice makes me a bit of a Dutch Uncle: Allow your Amarone at least one year of bottle age before you try it. I know . . . it’s hard to look at it just sitting there, begging to be drank, or at least tasted, but wine this big is not going to deliver smoothness or full aroma until it’s had a chance to integrate in the bottle.

Even at that, it’s not going to peak for several years, and should hold at least 5 after that — if you’ve used a top-quality cork and good cellaring conditions. If you absolutely must commit “vinfanticide” and drink it before a year, try to decant it at least an hour before service. This will allow it to open up a bit, and drop some of the more aggressive tannins.

I like Amarone paired with a classic Italian dish, Bistecca a la Fiorentina, essentially a four-pound porterhouse steak (hey, it serves more than one — sometimes . . .) very simply seasoned and grilled over oak or olive-wood coals. The richness and intensity of a well-marbled, bone-in steak provides a splendid backdrop for the power and complexity of a mature Amarone.

The slightly sweeter styles are best for after dinner, sitting on the deck with some quiet jazz or opera playing, and perhaps a few chunks of Parmigiano Reggiano cheese. Also, for those with lung capacity to spare, these styles go nicely with a contemplative cigar or a friendly pipe in the company of cheerful friends.

It’s during the quiet moments of thoughtful sipping that we can think back to the early adventurers who took their wine with them on the road, to fortify them against the giants of the world, and, sitting in the comfort of our homes, enjoying a glass, we can appreciate their pioneering ways, and the wines that survived for us into modern times.