Small Barrels, Unwanted Secondary Ferments, Natural Ferments, & Cold Stabilization

Q. I’m a fairly new home winemaker and I’ve been tempted by the smaller barrels I see for sale — some are just 5- to 10-gallons (19- to 38-L). They seem perfect for my batch sizes, but I’ve heard mixed opinions. How would aging a red wine in one of those compare to a standard 59-gallon (225-L) barrel? Am I going to run into problems, or can I get the same results in these less expensive and easier-to-handle sizes?

Ellen M. • Santa Rosa, California

A. This is a great question, and one that touches on the beautiful interplay between wine and wood. The short version is that the smaller the barrel, the more oak contact your wine will have. Because the ratio of wood surface area-to-wine volume increases as the barrel size goes down, the wine in a 5- or 10-gallon (19- to 38-L) cask will pick up oak flavors (and tannins) much more quickly than the same wine in a standard 59-gallon (225-L) barrique.

That can be a positive thing — if you’re after oak toast, vanillin, or spice characters, a small barrel can deliver them in a fraction of the time. But it can also be risky. With so much wood per gallon/L, a delicate red can easily tip from “nicely structured” into “over-oaked” before you know it. Commercial wineries keep a close eye on their barrel-aged lots for exactly this reason, and with a small barrel it’s even more important to taste regularly (think every week) rather than waiting months between samplings.

There’s another difference to be aware of, and that’s oxygen. Wine doesn’t just extract flavor from oak; it also breathes through the barrel staves. That gentle oxygen exchange helps soften tannins and develop complexity over time. In small barrels, oxygen ingress per gallon/L is again higher. This can be beneficial for a young, robust red that needs some taming, but it also means your wine could advance through aging stages faster than you expect. If the wine is light in body or already quite mature, it may tire quickly in a small cask if left for too long.

Some winemakers use a hybrid approach — aging part of the batch in a small barrel for oak and structure and keeping the rest in glass or stainless. Later they can blend to taste, adjusting the oak profile to suit the wine rather than letting the barrel call all the shots. The portion in stainless or glass, especially when kept as “breakdown containers,” i.e., as full as possible, serve as useful topping wine for the small barrel. You’re going to need it with the more frequent tasting regimen you’ll be implementing! Even with small barrels you need to top up regularly to minimize oxygen inside.

So yes, those little barrels can be wonderful tools, but treat them with respect. Their influence is stronger, faster, and less forgiving. With a careful hand (and frequent tasting and re-topping), you can absolutely make beautiful red wine in them — just don’t expect them to behave exactly like their bigger counterparts.

Q. Back in March I bottled a rosé that was quite acidic (think Muscadet acidic). There was no residual sugar, and the pH was 3.28. It had gone through coarse filtering, 1 micron, but not sterile filtering. Four months later I opened a bottle to find that it had gotten cloudy and fizzy. My wine had become a sparkling rosé. Could it have gone through malolactic fermentation or some other process?

Jack Kerr • via email

A. Thanks for writing in with your fizzing rosé mystery. I can see why it caught you by surprise — there’s nothing quite like popping open a bottle you meant to be still and finding it has turned into a sparkling version of itself. Let’s talk through what might have happened in your case.

You described a wine bottled in March, bright and very crisp, with no residual sugar and a pH of 3.28. You ran it through a one-micron filter before bottling but stopped short of a proper sterile filtration. Now, four months later, you’ve uncorked something that’s cloudy, spritzy, and decidedly different from what went into the bottle.

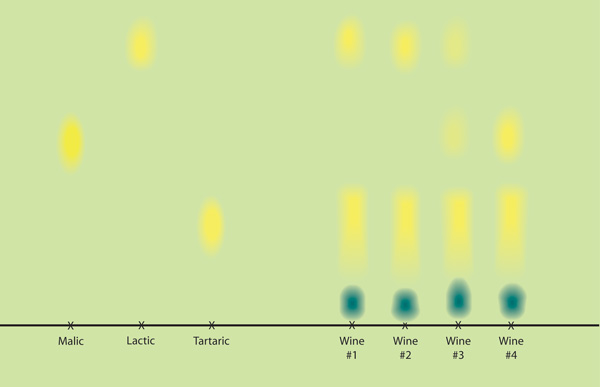

What you’re most likely seeing is a classic case of a secondary fermentation in the bottle. Even though your wine was dry, if it had any malic acid left in it, lactic acid bacteria could have survived the one-micron filtration and carried on their work after bottling. The process they carry out — malolactic fermentation — turns malic acid into lactic acid. It softens the wine, alters the mouthfeel, and just as importantly here, gives off carbon dioxide as a byproduct. That gas, trapped in the sealed bottle, is what made your wine sparkle when you opened it. The haze you noticed is another calling card for microbial activity.

The key detail here is your filtration. A one-micron cartridge will polish up a wine for the time being, removing a lot of particles and leaving it brilliantly clear to the eye, but it is not small enough to stop bacteria. True “sterile” filtration in the wine world only happens when the filter has pores of about 0.45 micron. At that level, you can reliably exclude most microbes — both bacteria and yeast. Without that finer step, there’s always a chance that a few tiny cells sneak through and set up shop in bottle.

Could yeast have been responsible instead? It’s much less likely. Since you had no residual sugar left, the yeast would have had nothing to feed on. At a pH of 3.28 — decidedly on the zippy side — and assuming your sulfur dioxide levels were in a normal, protective range, most spoilage yeasts would have been held at bay. That’s why I put my money on lactic acid bacteria here. They are uniquely comfortable working in a wine environment, and even though your acid level is high, they are robust enough to persist, especially when given the chance to slip through a one-micron screen.

Sometimes winemakers are tempted to stop malolactic fermentation (MLF) short or to bottle wine that hasn’t been sterile filtered, thinking that dryness and low pH will be protection enough. Usually things work out — but every once in a while, you get a surprise like this one. If you want to guarantee stability in the bottle, especially for high-acid wines that you’d like to keep crisp and fresh, sterile filtration at 0.45 micron is really the most reliable path.

Sulfur dioxide management also plays a role. Keeping your free SO₂ at the right level for your pH will help discourage microbial growth, though it won’t make up for incomplete filtration. Higher-pH wines need higher levels of SO₂ to be effective, and you don’t want to add so much that you smell or taste it. Your pH is so low that I think bottling with a free SO₂ of 30–35 ppm is great . . . but at that dose it’s still not a substitute for a sterile filtration.

So where does that leave you? Mostly with a great learning experience and a story to tell at your next tasting. Your rosé wasn’t “ruined” (many people love a little sparkle, after all) but it wasn’t what you had in mind. Next time you want a wine to stay perfectly still, make sure you either finish MLF completely and also protect the wine with SO₂, or keep it from ever starting in the first place with sterile filtration.

Q. I’m just starting out with my first batch of wine this year. I’ve heard a lot about “natural wine” and that being “non-interventionist” in the cellar is a good thing. Do I need to inoculate with a known yeast strain, or can I do an “indigenous yeast fermentation” like I’ve seen mentioned by some people online?

Barbara Blankenship • Costa Mesa, California

A. You’ve bumped into one of the more debated (and sometimes misunderstood) corners of winemaking: “Natural wine” and whether you need to inoculate with a known yeast strain. It’s a lively topic, and one that gets wrapped up not only in science but in marketing, philosophy, and even a little politics.

The first and most important point is this: All fermentations are natural. Whether yeast cells arrive from the air in your cellar or are added from a carefully selected commercial packet, the transformation of sugar into alcohol by a living microbe is always a natural process. There aren’t any awards given in the winemaking world for being “hands off” or not using the tools available to us as winemakers. What there are, however, are very real differences in predictability, reliability, and risk.

Some winemakers (and quite a few consumers) have been drawn to the idea that “indigenous” or “wild” yeast fermentations are somehow purer, less manipulated, or more authentic. That can be a romantic image, but it isn’t quite the full story. Yeast strains capable of carrying a fermentation all the way to dryness don’t generally come in on the grapes themselves. What arrives from the vineyard are usually species that can start a fermentation, but they tend to peter out after a few percentage points of alcohol. The yeast species (and it’s often a mix of strains) that can finish the job — members of Saccharomyces cerevisiae — are most often those that have taken up residence in a winery over time. That’s why established cellars (where fermentations have been happening for decades or more) are much more likely to have strong ambient populations (often those same “commercial” yeast strains, by the way) that can run a “wild” fermentation to completion.

For a first-time winemaker working in a new space, the microbial odds are not nearly so reliable. You might get lucky and your must may take off beautifully. You might also wait two days and find nothing much happening, giving spoilage organisms (like those that produce vinegar aromas or nail-polish-like ethyl acetate) a chance to grow unchecked. That’s one of the main risks of leaving your ferment entirely to chance.

Commercial yeast strains, on the other hand, are simply Saccharomyces cells that have been selected for certain qualities (good tolerance of alcohol, ability to ferment cleanly at cooler temperatures, low production of hydrogen sulfide, etc.). Inoculation with one of these strains isn’t cheating or forcing something unnatural, it’s giving your fermentation a safe and predictable start. There’s no shame in choosing a yeast that helps you get the wine you want. (In fact, commercial wineries producing bottles that cost many times more than your home batch are very often inoculating, because consistency matters to them too.)

That doesn’t mean there’s no room for curiosity or experimentation. When non-inoculation works, you can end up with layers of aroma and texture that feel especially tied to place. But that success often rests on an invisible foundation of microbial stability that comes only after years of fermentations in the same cellar. For a beginner, the risk of spoilage outweighs the potential reward, in my book. If you are curious, a good way to experiment is to split your fruit into two lots — try a native fermentation on a small portion and inoculate the rest with a commercial yeast. That way you’ll be learning without putting your whole harvest at risk.

Just be very clear-eyed and realistic about all of this. Yeast cells love to travel on equipment, on our hands, and in the air. They can’t easily be 100% cleaned off or excluded in the busy environment of a winery during harvest. Even if your “non-inoculated” batch turns out great, how do you know it wasn’t a few happy commercial yeast cells that got in and took over the fermentation? Keep this in mind when listening to others online or in your winemaking group romanticize about their “natural” fermentations.

There’s another angle to your question too: The way the term “natural wine” gets used in the marketplace. Right now, there is no formal definition of what makes a wine “natural.” Some producers define it by farming practices, others by what happens (or doesn’t happen) in the cellar. The danger is that the word gets used more as a marketing tool than as a technical description. Even worse is that it’s been used and is being used as a cudgel against other brands, that somehow someone’s wine is less-than because they chose to inoculate with a heritage yeast isolated from a famous cellar in France hundreds of years ago (looking at you, Pasteur Champagne yeast). Not intervening in the fermentation doesn’t automatically make a wine healthier, more authentic, or somehow morally superior. What matters is whether the winemaker is making careful, informed choices that fit their goals for the wine.

So, my advice to you is gentle but firm: Inoculate your first batch. Give your yeast a head start and set yourself up for a complete, clean fermentation. You’ll learn so much more from a healthy, successful process than from worrying whether something is going wrong. Later on, once you’re comfortable, you can play with native ferments and see how you like them. And if you want to call those experiments “natural,” you can — but know that your inoculated wines are every bit as real and valid, because every fermentation, at its heart, is a natural one.

Q. I’ve read a bit about cold stabilization for white wines, but I’m not sure I really understand what’s required. Some friends tell me just to put my carboy in the garage over the winter, others say it has to be a lot colder than that. Is there a reliable way for a home winemaker to achieve cold stability, or should I even bother?

Tom R. • Spokane, Washington

A. Cold stability is one of those topics that sounds simple on the surface but gets tricky once you look at the details. What we’re trying to prevent is the formation of tartrate crystals — little “wine diamonds” that can fall out in the bottle or even form on a cork if a wine gets chilled later on. They’re harmless, but consumers often confuse them with glass shards, so most commercial white wines are cold stabilized before bottling.

True cold stabilization requires dropping the wine to around 27–30 °F (-1 to -3 °C) for one to three weeks, depending on the chemistry of the lot. That consistent low temperature allows potassium bitartrate (cream of tartar) to precipitate out in the tank, after which the wine can be racked off the crystals and bottled with confidence. In a commercial winery, jacketed stainless tanks and glycol chillers make this possible. At home, however, it’s difficult to hold wine at those precise temperatures for long enough. A chilly garage might get you partway there, but unless you can verify the temperature and keep it steady, the results are usually incomplete.

Luckily, there is another option. Carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) is a safe and approved cellulose derivative that can be added to white wines to prevent crystal formation. Instead of forcing the crystals to fall out ahead of time, it interferes with their ability to grow large enough to be visible. CMC is odorless, flavorless, and stable, and it’s widely used in the industry as a finishing step for white wines. Do note, however, that it should not be used in reds or rosés — pigments and phenolics can react with it, leading to haze or instability.

For a home winemaker, CMC is often the best route. It spares you the challenge of precise chilling and gives you a stable, crystal-free white wine ready for bottling. Just be sure to follow product directions for dosage and mixing, and you’ll have a clean, clear wine without the worry of diamonds glinting at the bottom of the bottle.