Pressure in the Home Vineyard: How to measure and mitigate fungal disease

It is not lost on the well-informed winegrower/winemaker that fungi — ancient, single-cell organisms that have been on this planet hundreds of millions of years longer than humans — are our best friend in the winery and our worst enemy in the vineyard. How is that possible? Yeast are fungi, and the strains that ferment beer, wine, and even the base material for spirits are the most important industrial microbe the world has ever seen. Fermentation can be seen as “controlled spoilage,” whether making pickles or booze — it’s a way that humans have preserved agricultural harvests that are too bountiful to consume in a fresh form. But then there’s fungi like powdery and downy mildew, black rot and Botrytis — the scourge of both pro and amateur vineyardists the world over. Let me suggest that a conversation about yeast strains and winemaking might be a shinier and happier subject for an article, but helping you ferment is not my job here at WineMaker magazine. The last twenty years of this column has been dedicated to helping you grow clean and beautiful wine grapes that become the base ingredient for delicious wine.

I consult on small-scale (and commercial) vineyards from sea to shining sea in the United States, from Santa Barbara to South Carolina. In my travels and at the annual WineMaker Magazine Conference, folks show me their worst vineyard problems and challenges, and more often than not they are fungal diseases and finding successful strategies to mitigate this disease pressure.

“Something happened to my vineyard this year, and I can’t figure out what ruined my fruit,” is a very common complaint, and usually without even seeing the vineyard I will assume that mildew or rot has won the battle of the vintage. I try to be gentle in my consultation, but the final message should be clear: You failed to manage your spray schedule and fungicide program and as a result you wasted an entire year in the backyard vineyard.

Powdery mildew weakens the skins of the grapes as the fungi perforate the skins to drink liquid from their host.

The biggest change in my own vineyard management practices in the 20+ vintages that I’ve managed commercial vineyards has been how to handle the vineyard between budbreak and bloom. We send the crew into the vineyard much earlier now, and have found that the early work we finish is much more economical than coming back and trying to “fix” the canopy after it has filled the trellis. In this spirit, I hope to share some of our early-season “pro tricks” in vineyard management and describe how getting into the vineyard early can save you lots of hassles at the middle and end of the growing season.

Four Horsemen of the Viticultural Apocalypse

Know thine enemy. Let’s take a look at the four most common and damaging of fungal pathogens in North American vineyards, understand their growth patterns, and then later we will discuss specific best-practice fungicide regimes for keeping that fruit clean and your wine medal-worthy.

Powdery Mildew (Uncinula necator): As a Pinot Noir and Chardonnay specialist in the cool, coastal viticultural areas of Santa Barbara County, California, powdery mildew is my primary fungal threat in the vineyard. Left unchecked and unsprayed, not a single berry would be viable for winemaking because of the damage “PM” would cause. The frosty, white filaments and spores are almost impossible to see when the infection begins, and as a result, once the infection is visible to the human eye, your vineyard is pretty much screwed for the vintage. If you can see it, it will negatively impact your vintage. Once sprayed and destroyed, the mildew turns a dull grey. By the time the grapes soften and change color (veraison or around 17–18 °Brix), the fruit becomes invulnerable to PM infection and sprays for powdery can end. Powdery mildew weakens the skins of the grapes as the fungi perforate the skins to drink liquid from their host. If you see mysterious black spots on your white fruit as it ripens, or the skins crack mysteriously, you likely had a PM infection that did not become visible — but even slight mildew infections knocked down by fungicide can still cause these problems. So again, NEVER wait until mildew is visible to start your fungicide spray program. It’s like cheating at poker — if you can see it, you’re already a loser. Like most fungal infections, PM thrives in a climate between 70–85 °F (21–30 °C). We will learn later how to assess fungal pressure mathematically to plan our sprays. Powdery mildew can be controlled without a pesticide permit with a number of easily obtained materials: Mainly stylet oil and wettable or powdered sulfur. Sprays should commence at 4–6 in. (10–15 cm) of shoot growth and persist through bunch closure until 50% veraison. Follow label instructions carefully.

Downy Mildew (Plasmopara viticola): Especially virulent in Gulf Coast states, and slowly moving north to areas with high humidity and warm temperatures, downy mildew, or DM, is a bit trickier to mitigate in the winegrape vineyard than powdery mildew. Powdery mildew usually sporulates and spreads earlier than downy mildew, and some vineyards find that using early-ripening varieties combined with open canopies (reduce humidity) can be quite helpful. DM does not respond to sulfur applications like PM, so copper sulfate sprays may be your main weapon. These are usually applied early in the season, but may have to be added to later-season sprays to make sure the DM spores are in check or dead before their normal summer spore explosion. Over-application of copper sulfate can negatively impact soil health, so make sure to use copper sprays only when needed and at the exact dilution suggested on the packaging. Higher concentrations do not work better and can be bad for the vineyard and your soil.

Botrytis (Cinerea) or Shoot Blight: Noble or nasty? Botrytis is famous for producing some of the greatest dessert wines in the world: Sauternes and Alsatian Sélection de Grains Nobles to name a few. When Botrytis is noble, it is allowed to encompass clusters late in the growing season until they are mummified by blue-grey mold. Why would anyone do this? The answer is a miraculous impact on the skins and water in the grapes. Botrytis makes micro-perforations in the grape skins (usually Sémillon or aromatic white wine varieties) and the fungi feed/drink the water inside the berries and leave behind the sugars and other compounds with minimal oxidation. So when you press “Bot” clusters, you get a muddy syrup that can be as high as 50 °Brix! Rack off the muddy spores from the amber syrup, ferment to around 11–12% alcohol and then sterile filter the wine, and you will have an amazing sticky with sexy honeyed notes. That’s the noble nature of Botrytis . . . but now let’s talk about the nasty side of Bot. Ever see your young, freshly growing spring vines show a black, necrotic (dead) spot on the tendril or growing tip? We call that “Spring Blight” or “Early Season Botrytis Infection.” Bot also likes to infect tender young tendrils and shoots, which is another reason we like to add some copper to the first few sprays of the season, starting at 4 in. (10 cm) of shoot growth on average. The copper will also manage ice-nucleating bacteria and give a few extra degrees of frost protection. Early stylet oil application will also starve the Bot of oxygen and keep the spores from, well, sporulating and spreading their nastiness.

Black Rot (Guignardia bidwellii): As a West-Coast viticulturist, I am happy to say I have never seen black rot in person, but I get a lot of questions about it during my grape growing boot camps at the WineMaker Magazine Conference. Black rot used to be limited to Eastern North America, but just like phylloxera and a few other pathogens/insect vectors, we have gifted this nasty fungi to Europe and Asia (sorry!). The symptoms are circular, brown spots on leaf blades, stems and any vine tissue, and impacted berries turn brown and stunted, with black spots. The berries turn into unripe raisin-like mummies. A warm summer rain is often the main culprit of spreading the disease. Control is achieved using “Bordeaux mixture,” which is copper sulfate carefully and professionally mixed with slaked lime, also known as calcium oxide. This spray is preventative only, and will not be effective against active infections. As with all fungal diseases, once you notice it, it’s probably too late to control it and make the best wine out of your vineyard. Captan fungicide is also effective in combating black rot, but it is a restricted material in many states and counties. Check with your local agriculture commissioner on your options for home-vineyard application. Keeping an open canopy (not too much or you’ll burn your fruit) so wind and sun can penetrate the canopy and keep humidity mitigated will go a long way to keeping black rot off your fruiting zone.

Face the Challenges Ahead

Fungicide Resistance: Elemental sprays versus synthetics. This is easy stuff and one time when the hippies got it right. I am well-known for lamenting that home vineyardists are very limited in their choices for vineyard fungicide sprays. The amazingly effective (and expensive) synthetic fungicides that we cycle through in pro vineyards (‘strobilurins’ like Flint, Rally, etc.) require permitting, but have amazing longevity, sometimes allowing nearly a month between sprays. But, fungi in the vineyard are becoming very adept at mutating and developing resistance to these materials, making it necessary to cycle through a half-dozen active ingredients per vintage to minimize resistance. ‘Elemental’ materials such as sulfur, copper sulfate, and mineral (stylet) oil are not synthesized and as a result, fungi cannot develop a resistance to them. Read that again. Sulfur, copper, and stylet oil will be as effective in your vineyard twenty years from now as they will in the 2019 vintage, even if you use them exclusively for fungicide. These materials tend not to have the same long-lasting action, and must be sprayed more often, sometimes as often as every week. Also, and this will play into the next section, copper and stylet oil MUST contact fungi to disrupt them. Sulfur also needs it to be warm but not hot to function, as the mode of action is to produce sulfur dioxide gas in the canopy — which disrupts the fungus’ ability to grow and sporulate.

The Penetration Problem: Here’s another incredibly common failure in home vineyards. I get a consulting call to come look at a vineyard and the crop has been decimated by fungi, usually powdery mildew. “But I sprayed every 14 days!,” the owner laments. “Can I see your spray rig?,” I ask. They break out a backpack sprayer with a hand-operated lever to create pressure. Between the under-powered backpack sprayer and incomplete or non-existent canopy management, there’s little wonder why the mildew wins. Never pull more leaves than are safe to keep the clusters from being sunburned, but do pull as many leaves from around the cluster as possible to open up the fruiting zone to maximum wind and sunshine — especially under and around the clusters, leaving upper leaves like a sombrero to protect the clusters from the hottest hours of the day (10 am–2 pm). An open fruiting zone (never more than 1 leaf between the sun and the cluster) will make it harder for the mildew/rot to make a foothold in the canopy (fungi hate sun and wind), but also it will allow your sprays to penetrate the leaf-layer and make contact with the clusters. If you are spraying and any part of your cluster stays dry, that part has not been protected by stylet oil or copper sulfate, which require contact to be efficient/effective.

And as you are expecting, I do suggest trying to find a spray-rig that can produce enough PSI to penetrate and properly soak the clusters and the tissue/leaves/stems in the fruiting zone. A high-end backpack sprayer may even require spraying on both sides of the vine row for proper coverage, and a gas-powered or electric-powered spray rig (on an ATV or wheeled cart) may be a better issue for those that continue to struggle with mildew/rot infections every vintage. So open up that canopy as much as you can without burning the fruit, and get a spray rig that really saturates the canopy on both sides!

The Holy Trinity of Fungicides

We had the Four Horsemen, so now it’s time to look at the solutions, all of which are elemental kind and as such, cannot cause resistance.

IMPORTANT: Take care with mixing and application and wear overalls, eye protection, and a respirator when spraying anything in the vineyard, besides water.

Sulfur: Likely the most common fungicide in vineyards worldwide, wettable or powder sulfur applications are effective in warmer temperatures (59–82 °F/15–28 °C), as the material needs to be made volatile into sulfur dioxide for control of fungal pathogens in grapevines. Sulfur does have the benefit of not having to contact the spores and filaments of mildew (contact is beneficial though), but should not be applied in hot spells (over 85 °F/30 °C), which may cause injury to the vine, so sulfur is better as a spring/warm weather fungicide. Sulfur is basically only effective for powdery mildew abatement, and always before an infection is visible. A good application of sulfur can give good protection in a vineyard between 7–14 days, depending on weather and precipitation.

Copper Sulfate/Bordeaux Mixture: Best applied in dry weather, as copper does wash off of grapes and tissue readily. Effective for black rot, and also shows some efficacy in limiting Botrytis. Black rot applications should be late spring/early summer and for Botrytis and frost mitigation, use as the first spray of the year at around 4 in. (10 cm) of shoot growth. Limit the amount to an application (or two) at the beginning of the season, and then perhaps as weather gets warm/hot if you are in an area that black rot can raise its ugly head.

Stylet Oil: Stylet (mineral) oil cuts off fungus from their oxygen supply and basically suffocates the pathogens, a mode of action called a smotherant. Stylet oil is both a preventative and an eradicant — but as we’ve learned, let’s keep the vineyards clean instead of trying to fix vines/fruit that have already been compromised. For many highly successful home vineyardists I’ve talked to on the West Coast, organic stylet oil is the bread and butter of their fungicide regime.

Conclusions

FOLLOW LABEL DIRECTIONS. Never assume increasing the concentration of a spray material will make it more effective. The opposite is often true and can cause vine injury or worse. If the company could suggest you use more of their product, don’t you think they would? I always suggest to my consultation clients to start their sprays using the minimum interval indicated on the label. If it says, for grapes, 7–14 days, start at 7 and if your fruit is pristine and the wine is great, maybe go to 8 day intervals next year. Err on the side of safety, coverage, and PSI pressure in your spray rig.

The most important element is observation and record keeping. Try to keep a running log of high and low temperatures, levels of leaf-removal and canopy gaps, when and where mildew/rot rears its ugly head and adapt. Spray hard and often until you have a disease-free year, and then lighten up and spread out the applications slowly over time when you learn what the vines need and how to keep them free of fungi pathogens.

Powdery Mildew Fungicide Application

Let’s learn the University of California’s protocol for initiating a fungicide application for powdery mildew. For most of you, this will mean applications of a sulfur spray. The following is verbatim from the University of California Integrated Pest Management on their website (http://ipm.ucanr.edu/PMG/r302100311.html):

When there are 3 consecutive days with 6 or more continuous hours of temperatures between 70 and 85 °F (21 and 30 °C) as measured in the vine canopy, an epidemic-level of powdery mildew infection will have begun in your vineyard.

- Starting with the index at 0 on the first day, add 20 points for each day with 6 or more continuous hours of temperatures between 70 and 85 °F (21 and 30 °C).

- Until the index reaches 60, if a day has fewer than 6 continuous hours of temperatures between 70 and 85 °F (21 and 30 °C), reset the index to 0 and continue.

- If the index reaches 60, an epidemic is under way. Begin using the spray-timing phase of the index. (In other words, spray sulfur or stylet oil in the vineyard)

Spray timing

Each day, starting on the day after the index reached 60 points during the start phase, evaluate the temperatures and adjust the previous day’s index according to the rules below. Keep a running tabulation throughout the season. In assigning points, note the following:

If the index is already at 100, you can’t add points.

If the index is already at 0, you can’t subtract points.

You can’t add more than 20 points a day.

You can’t subtract more than 10 points a day.

- If fewer than 6 continuous hours of temperatures occurred between 70 and 85 °F (21 and 30 °C), subtract 10 points.

- If 6 or more continuous hours of temperatures occurred between 70 and 85 °F (21 and 30 °C), add 20 points.

- If temperatures reached 95 °F (35 °C) for more than 15 minutes, subtract 10 points.

- If there are 6 or more continuous hours with temperatures between 70 and 85 °F (21 and 30 °C) AND the temperature rises to or above 95 °F (35 °C) for at least 15 minutes, add 10 points. (This is the equivalent of combining points 2 and 3 above.)

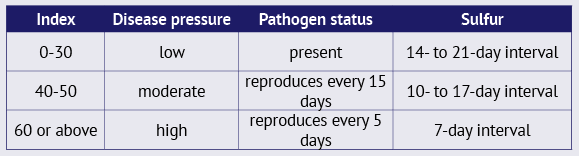

Use the index below to determine disease pressure and how often you need to spray to protect the vines. Spray intervals can be shortened or lengthened depending on disease pressure, as indicated in the table below. The schedule assumes adequate coverage; the use of calibrated sprayers and sufficient gallons per acre appropriate for type of sprayer and vineyard trellis.