Dirt Don’t Lie: The impact of soil on vineyards and wine

In general, wine grapes of the Vitis vinifera family grow between the 30th and 50th parallels of latitude where the average temperatures are between 50 and 70 °F (10 and 21 °C). Grapes are grown on stony hillsides with almost no soil, the vines clinging and fighting for every inch of purchase. Grapes are grown in deep, fertile soil where they produce astounding amounts of vigor (and hopefully fruit!). Vineyards are planted in soils based on sand, clay, silt, schist, chalk, diatomaceous earth, limestone, or a mix of these soil constituents.

The most profound impact of soil on a vineyard is vigor. While soils may also impact disease (from pests, bacteria, or virus), grapeskin thickness, erosive potential, heat reflection (especially if the topsoil is stony); I will argue that vigor is the primary consideration of how dirt influences the vine, and thereby, the wine.

History

The Romans loved to conquer land and plant vineyards. From Sicily to England, the Romans enjoyed drinking wine from all over their empire — even the Roman Centurian’s staff was called the Vine Staff and was made from a thick vine stalk and used to beat lagging soldiers during marches and exercises. It was a statement — were they conquering for the Glory of Rome or for the Glory of Bacchus? The answer is both!

But back to dirt. I mention the Romans because they knew their dirt. When a new land was conquered the Romans would make quick work of establishing a system of agriculture that would yield the best results for the army, for Rome, and for the soldier that would be granted the management (and sometimes ownership) of the newly conquered farmland. The take-home message is what and where they planted.

The most profound impact of soil on a vineyard is vigor.

The fertile valleys between hills and mountains tend to be very high-production and high-fertility agricultural areas. The soils tend to be deep and rich due to the alluvial action of weathered rocks and soil particles washing off the hills and mountains and being moved by water and wind into the valleys. These fertile valleys would become the grain basket for the Roman Empire — and what we would call row-crop farming was practiced in its nascent form in these fertile plains and valleys.

Moving from these high-vigor soils into the foothills that surrounded them, the Romans saw that grain, fruit, and vegetable crops failed to produce healthy yields once the soils became rocky and uneven. It was on these rocky, mixed-soil hillsides that the Romans planted olive trees, which require almost no topsoil for production, and between the olive trees, they would plant vines for wine production. A strategy that designated poorer soil for olives, and then saw that the olive trees worked to help the vines trellis themselves in the olive trees and between, initiated a style of viticultural development that changed the world of wine.

An unintended (?) side effect of putting Roman vineyards on poor, rocky soil, was that the vines struggled, grew smaller than when planted on deeper, richer soil, and produced smaller growth, smaller clusters, and smaller berries with thicker skins. Hillside and mountain-grown wines gained a reputation for quality and deep flavor, which increased the frequency of the practice of planting hillside vineyards until it became well-known to almost every vine farmer in Rome, and then in post-Roman Europe, that vines grown on inhospitable, rocky hillsides often produce very expressive wines.

On average, soil on our planet breaks down to these surprising percentages:

• 25% air (pores, or gaps in the soil)

• 25% water (obviously depending on water-holding capacity and availability)

• 45% mineral particles (inorganic: Clay, silt, and sand)

• 5% organic matter of which there is:

º 80% humus (plant matter broken down by insects, bacteria, etc.)

º 10% plant roots

º 10% soil organisms (such as bacteria, insects, worms, nematodes, etc.)

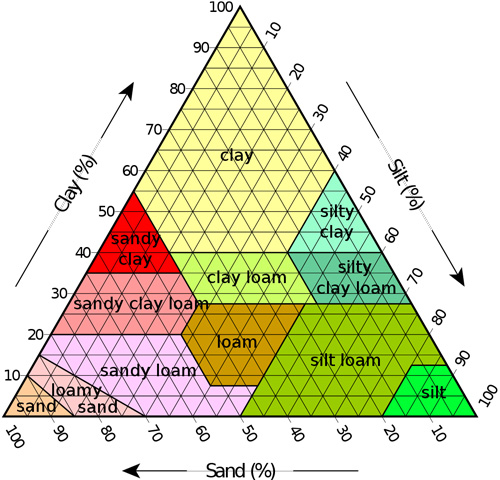

From the chart above, we can measure the mineral particles by type (clay, silt, and sand) and percentage to determine what kind of soils we have in our own backyard vineyard. You may recognize these next descriptions if you have ever attended one of my Boot Camps (psst . . . next one is in San Luis Obispo in 2022).

Soil Definitions

Clay: Smallest soil particles, phyllosilicate materials, mineral in origin, formed by chemical weathering, holds water the longest of all soil types.

Silt: Larger than clay, smaller than sand, commonly formed on the bottom of a water body, consists mainly of feldspar and quartz — rock dust.

Sand: Usually silica quartz (resists chemical weathering), largest soil particle, great drainage, poor fertility.

Loam: A combination of the three soil constituents in various degrees. Ideal for gardening and agricultural uses because it retains nutrients and retains water while still allowing water to flow freely.

Determining Your Soil Type

How lucky for you that there is a very cheap and relatively fast way to test your soil constituents, and then determine exactly what kind of soil type you have by matching it with the triangle chart below.

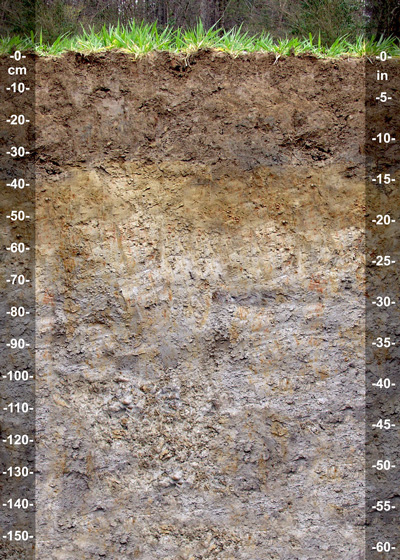

- Fill a large glass Mason jar half way with your soil, using dirt from between 10–20 in. (25–50 cm) under the surface. (You can also test 18–30 in. (46–76 cm) and 36–48 in. (91–122 cm) if you want to see how the soil changes, as these are the depths that will have a greater impact on vineyard vigor and wine flavor.)

- Add clean water (tap is fine) to the soil in the jar, leaving at least 1 in. (2.5 cm) of headspace (air).

- Screw down the lid tightly and then shake vigorously until the muddy water has completely been broken down and no lumps/clumps exist.

- Leave undisturbed overnight.

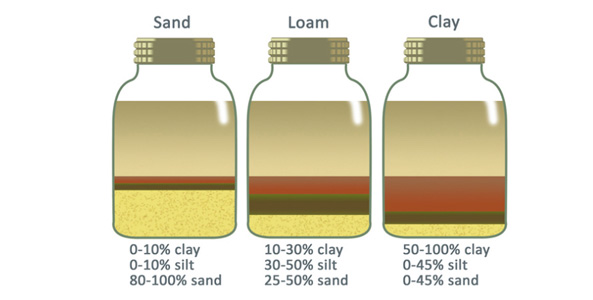

- In the morning, you will see that the soil particles will have separated into clay on the top layer (finest particles), then silt in the middle layer, and sand on the bottom.

The graphic above gives you the idea of what a sandy-, loamy-, or clay-based soil will look like in the finished jar. You can also measure the depth of each constituent in millimeters in ratio with the entire soil depth and get exact percentages. With those percentages you can define your soil exactly on the previous chart by applying those percentages.

I’ve Defined My Soil Type, Now What?

Each type of soil has impacts on vine physiology and resulting wine style. The following descriptions are generalized and will help lead us to a broad understanding of how soil impacts viticulture. Site specificity, of course, has a myriad of influences, so we are simplifying a single aspect of farming to understand soil.

Sandy Soils (Sand, Sandy Loam): Simply put, sandy soils are great for drainage, retain heat well, but generally have very low fertility, require supplemental irrigation in all but areas that get lots of summer rainfall, and commonly have difficulty in exchanging nutrients. Sandy soils are already deficient in nitrogen, potassium, and phosphorus: The macronutrients of plant growth and regulation. Add to that that vine roots cannot absorb nutrients from phyllosilicate because it lacks a positively-charged ion (cation) to make that exchange.

Sandy vineyard soils tend to make pale red wines in warm regions and highly aromatic wines (that can produce good color) in cool climates. Sandy and sandy loam soils produce some of the best US Pinot Noirs from coastal areas: Santa Maria, Sta. Rita Hills, Sonoma Coast among them. The greatest vineyard in Barolo, Italy (Nebbiolo in this case), Cannubi, is grown on sandy soils, with just enough clay to allow some nutrient exchange to help the vineyard struggle, but thrive. Sandy soils also tend to be more resistant to major vine pests like Phylloxera.

Loamy Soils: Loam is a gardener’s dream. It is an equal mix of clay, silt, and sand with organic material (humus) mixed in. By itself, loam is too vigorous of a soil to grow quality winegrapes. It would be the soil that the Romans would plant grain, fruit, and vegetables. The magic of loam is how it impacts mixed soils. Sandy loam, clay loam, and silt loam tend to make up the greatest wine soils in the world. The combination of sand’s drainage, clay’s ability to help a vine uptake nutrients as well as water-holding capacity, and silt also helps with heat retention and water holding.

Clay Soils (Clay Loam, Sandy Clay Loam, Silty Clay, Silty Clay Loam): Clay is the soil engine for water holding and efficient uptake of nutrients by the roots. Clay provides the chemical means for a vine to uptake nutrients, which is called cation-exchange capacity, or CEC. In general, the higher the clay content, the higher the CEC. Clay also keeps soil cooler and wetter, and holds water the longest of any soil type. Calcareous clay soils are rare in the world, but when they have the right location and aspect, produce some of the greatest wines in the world including Barolo, Burgundy (Marl soil), and much of the Napa Valley. In general, clay vineyard soils produce dark and structured reds.

Silty Soils (Silt Loam, Silt): In a perfect wine world, all silt soils would have limestone in them, as that tends to produce the highest quality wines on silt soil. Decent water-holding capacity, heat retention, and slower root development are noted in vineyards planted on silt-based soils. Silt soils tend to produce softer, rounder wines that tend to lose their acid a little earlier than on other soil types. The Willakenzie soils of the Willamette Valley, Oregon are well known silt-clay soils for producing high-quality Pinot Noir and other wines.

Putting it All Together

Defining your soil is all well and good, but how can we use this knowledge to grow and make better wine?

• When purchasing grapes from a local vineyard, know the soil type so you can monitor water application, vigor, and how the soil type will impact sugars, acid, and your pick date. For example: Heavy clay soils can be dry farmed in areas where sandy soils could not, and you may ask for irrigation to be stopped early on clay soils for full sugar development and a touch of dimpling for concentration. Sandy-soil types will have to be irrigated much more often, and likely fertilized more than clay or silt soils. Plus, filling a jar with dirt, and eventually having the soil skills to pick up a handful of dirt and watch it fall back to the earth just looks cool, and will set you apart with your geekiness.

• On your vineyard, each soil type has some management bonuses and challenges.

• Sandy soil, as previously mentioned, always requires more water (it zips right through the soil) and some added fertilizer (if the vines aren’t growing 12–15 leaves per cluster on average). I prefer building sandy soils instead of chemically fertilizing, using compost and organic materials like bat guano or fish emulsion. Don’t worry, they won’t make the wine smell!

• Silty soils are fairly rare in the world of viticulture, but they act a bit like clay. They hold water better (you could say they are poorly drained), are poor at exchanging nutrients, and they have a vigor-limiting aspect of restricting root growth because of a lack of soil pores (air). Expect more water-holding, but more vigor, than sand. Adjust your viticulture on silty soils to the vigor it produces. Reduce water in highly vigorous vineyards (10 ft./3 m + of cane growth on average per shoot) while keeping up with both canopy management and basal/lateral shoot removal.

• Wet clay soil stays wet a real long time. You may think it’s dry and then your boots break through the crust and down you go . . . sploosh! Clay soils often have increased vigor because of the high CEC as described previously, and there’s not much you can do to dry out wet, vigorous soil. If you have dry summers you can reduce or even try eliminating adding irrigation water, and just like with any vigorous vineyard the keys to success are hedging, lateral and sucker removal, and canopy management for an open, sun-flecked fruit zone. The benefit of a vigorous vineyard is using a trellis system (like the Lyre or Quadrilateral) to harness that vigor and turn it into massive amounts of fruit for winemaking.

A 118-year-old character in one of my favorite television shows, Futurama, once said: “I’m old as dirt, and dirt don’t lie!” It was one of those found poems that had no intention to have meaning in the world of wine and vineyard management, but that didn’t stop me from putting it on a few t-shirts.

In the world of wine, dirt (pardon the analogy) is a rabbit hole that’s as deep as you want to go. Soil microbiology is showing that the “life in dirt” is often as important as the soil’s constituents. The organic and inorganic do a stunningly complex dance under our feet and around every root of every vine. Wines are being planted on new soil types every day, and even after almost 10,000 years of vine domestication under our collective human belts, we are literally just scratching the surface on a science that defines the potential quantity and quality of every wine in the world.