Managing Acidity Through MLF

The malolactic fermentation (MLF) is a conversion by specific bacteria of malic acid to lactic caid with an associated reduction in total acidity and other flavor changes. This broad-based definition is seemingly the tip of the iceberg, but summarizes what is happening at a molecular level in the wine. Buried in the definition is understanding of what the implications are because of the MLF, which includes some positive and some negative attributes winemakers must consider. The MLF can contribute to increased microbial stability, potential improvement in mouthfeel, flavor changes based on decreased acidity and increased pH, and possibly a decrease in aging potential.

From a winemaking standpoint, MLF is a tool to use in developing the overall structure of a given wine. Notably, acidity in wine is contributory to the overall structure and should balance between phenolic expression as well as the flavors present. Every wine has its identity and that is part of the science and art of winemaking.

Where Does Malic Acid Come From and Why is it Important?

To start, we need to talk about the two major acids in grapes — tartaric acid and malic acid. Both are synthesized by the vine as a result of photosynthesis, where the vine takes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and builds carbon-based compounds. Sunlight and carbon dioxide being the aboveground building blocks for all plant compounds, in addition to water and the nutrients in the soil for which the plant grows on. The annual cycle of the grape consists of budbreak, flowering, fruit set, veraison, ripening, and then on to dormancy.

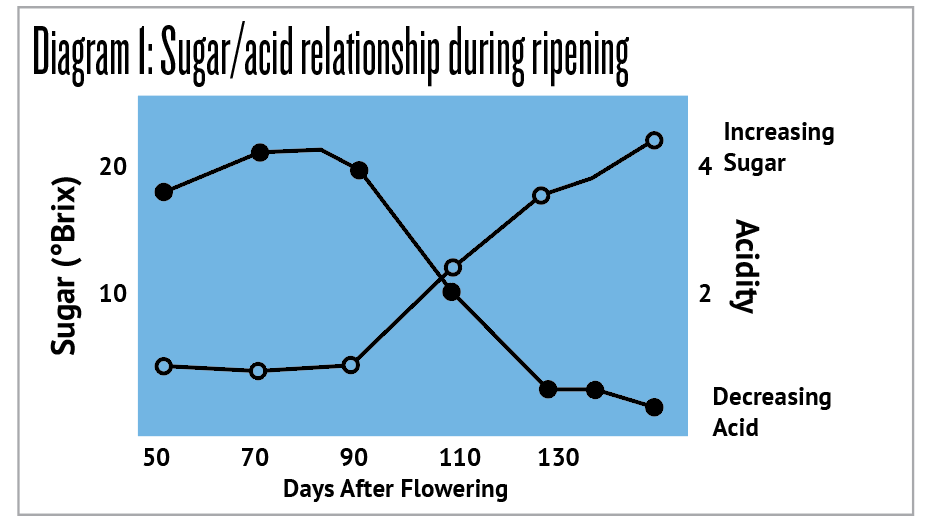

For this article we focus on veraison as the defining moment in malic acid metabolism. Pre-veraison, glucose is synthesized via photosynthesis for vine respiration for energy, while acids like tartaric and malic begin to accumulate in the berry. Tartaric acid is the most abundant acid in the grape. Maximum malic acid concentration within the berry occurs at veraison. Then after veraison, malic acid becomes the major carbon source for berry respiration while photosynthesis is directed towards the accumulation of glucose (sugars) and other flavor compounds in the berry. Malic acid levels at harvest vary by variety and harvest timing. They will continue to decline for berry respiration the longer a cluster stays on the vine. At harvest, concentrations can be less than 0.5 g/L or up to 9 g/L.

The sugar/acid relationship during ripening is simplified in Diagram 1.

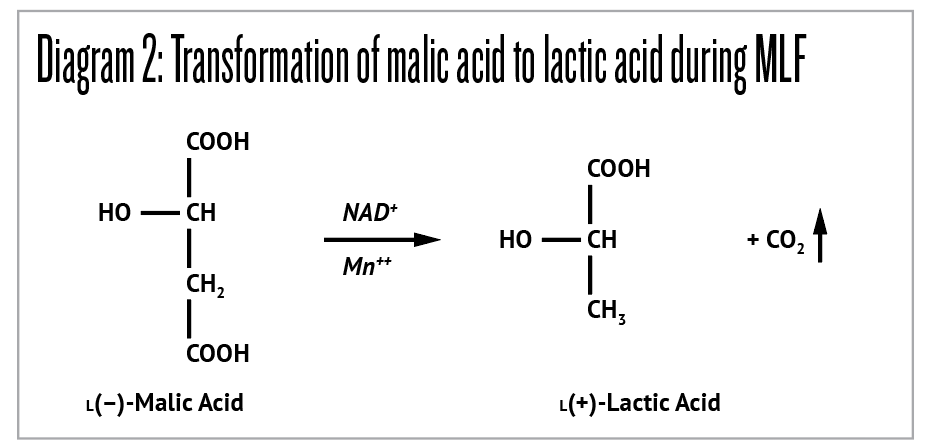

The MLF

Malic acid (4-carbon) is converted to lactic acid (3-carbon) via decarboxylation. The process is carried out by bacteria and some yeasts. The most common bacteria are of the Oenococcus genera, however there are several other Lactobacilli capable of performing the conversion, some in a positive way, others in the form of spoilage. The chemical description is illustrated in Diagram 2.

The MLF conversion by bacteria is influenced by several factors. The bacteria are sensitive to sulfur dioxide (>20 mg/L), perform less efficiently or slow at temperatures below 68 °F (20 °C), and alcohol levels above 15% ABV. Yeast strain can also have an inhibitory effect. The specific yeast’s metabolism can produce inhibitory peptides, medium chain fatty acids, and high levels of sulfur dioxide or lactic acid. The recent popularity of Metschnikowia pulcherrima for its bioprotective qualities will also have an effect. Metschnikowia is often used in a pre-alcoholic cold soak application. When selecting a yeast, and considering if you are planning an MLF, consult the manufacturer’s yeast charts to determine if the yeast is MLF-friendly. This information can also be obtained on the technical data sheet for the specific yeast.

To monitor the MLF progression, carbon dioxide is a byproduct of this conversion, so if the fermentations are done sequentially, that makes it very easy to monitor. Look for the gas evolution. Running a concurrent MLF along with the alcoholic fermentation may be indicated for high sugar musts. Once the yeast fermentation is well established, inoculate with the ML bacteria. When the yeast fermentation is complete, measure the malic acid concentration and check the progression with ML chromatography.

The choice of yeast and/or bacteria is yours based on your specific conditions. Many commercial bacteria strains are marketed with a variety of fermentation requirements similar to what you would see with commercial yeast strains. There are sulfur dioxide- and alcohol-tolerant varieties produced by many manufacturers. These may be suggested for high-sugar musts where a high-alcohol wine is desired. There are also different flavor contributions. Some strains produce higher levels of diacetyl (butter) than others. My go-to MLF strain is CHR Hansen CH16. As a commercial winemaker, I work for product consistency as most of our lots are small, so trying something new, and not getting the perceived effect might not be good for that brand.

Why is the MLF performed?

Wine style is probably the most important consideration for MLF. Preserving acidity or preventing deacidification. Acidity adds structure. Too much, the wine is tart. Too little, the wine is flat. The other components of wine structure consist of flavor and tannin expression. A trifecta in the winemaking world. But all grapes are different, and seasonal variations are commonplace. Every vintage takes some thought.

One notable premise of the MLF is that if the malic acid concentration is deleted, and all the sugar is fermented, then with all notable fermentables gone, the wine is theoretically microbially stable. What else is there to feed an organism? That’s a loaded question and beyond the scope of this article. But performing a willy-nilly MLF conversion, just because that is what the book says to do, is not part of the “art of winemaking.” What are you trying to achieve?

Beginning at the grape stage, I look ahead to where I envision a particular wine in, say, three months. I assess the titratable acidity (TA), and if I have access to the data, I look at the malic acid concentrations. Low-acid grapes might require a tartaric acid supplement. Targeting a final TA of 6–7 g/L is generally my goal. Common now is the availability to home winemakers of malic acid testing kits (Vinmetrica and SentiaTM offer these). With the malic acid concentration, you now have an idea of the percentage of acidity that would be removed if MLF was performed. You can judge whether to carry out full, partial, or no MLF at all. Taking the MLF to completion is generally indicated for high-TA wines. Grapes with low TA will likely not require any MLF, and perhaps even a tartaric acid supplement. This is the hardest aspect of winemaking to generalize the various winemaking regions across the world. There is no single recipe.

In the presence of all this technology, do not forget about the effect of taste. Wines do not read books, so you need to bring your own taste buds into the picture. Predicting how much deacidification is tricky. Focus on two distinct sensory characteristics — fat and flabby (low acid) versus too tart (high acid). The answer lies somewhere in between. Rather than just running a full MLF conversion, it may be necessary to stop it when the desired mouthfeel structure is found. Halting or inhibiting the MLF is done by adding sulfur dioxide up to 50 mg/L and chilling the wine. Some advocate adding lysozyme to the wine, however this will strip tannins and is essentially a waste of time and money because lysozyme is not a long-term protectant. Sulfur dioxide is far more effective in that it is antimicrobial and protects against oxidation if suitable levels are maintained in the wine. Sulfur dioxide effectiveness is pH-dependent, with lower pH needing less free SO2.

MLF does not always go according to plan. High-sugar musts can sometimes result in a stuck alcoholic fermentation, which is also inhibitory to the MLF. This is a prime condition for spoilage by what is termed as “ferocious Lactobacilli.’ Specifically, Lactobacillus kunkeii, named for renowned UC-Davis professor Ralph Kunkee. Dr. Kunkee discovered this organism in wines and traced it back to honeybees. It is beneficial to bees and their hives, but can inhibit yeast fermentation and will produce acetic acid from sugars. It is resistant to SO2 once established in a stuck wine! The best prevention is to sort out bad fruit prior to fermentation and adjust the sugar of the must for a potential alcohol level below 15%.

Given that winemaking is subject to vintage-to-vintage differences, we must all be aware of the various challenges already present or coming with respect to global warming. Warmer climates, from a winemaking perspective, require winemakers to preserve acidity. Either through viticultural practices or supplemental tartaric acid additions after harvest, if permitted. Depending on the viticultural area, this may or may not be permissible under local regulations. For example, in the United Sates, wineries are permitted to supplement juice/must or wine with tartaric, malic, or citric acids. Whereas, in the EU acidity adjustments are strictly regulated, and in most cases, not permitted. As home winemakers, you face none of the regulations and should be guided by producing the best-tasting wine possible.

A 2023 study conducted in Bordeaux, France, focused on breeding Saccharomyces strains to produce malic acid. Some studies have shown an increase of as much as 3 g/L in malic acid concentration during fermentation. 1 The significance of this research is tremendous. Preserving the harvest date acidity and then adding to it! From a winemaking standpoint, if these strains become commercially available, the yeast is used for the alcoholic fermentation and the MLF is evaluated based on the acidity and taste profiles after fermentation. I really look forward to seeing the outcome of this research as it could change how winemakers respond to global warming while preserving the character of the growing region.

In closing, the intricacies of the MLF are really too numerous for a simple generalization. Being consistent in your winemaking practices goes a long way to troubleshooting if you find yourself in a pinch. Early in my winemaking years I had a Zinfandel that I persisted in attempts to get the MLF completed. Several inoculations with freeze-dried cultures, I even built up an ML bacteria culture. Nothing worked. I talked with Dr. Kunkee about it. He understood I was throwing the book at it to no avail. He summarized it as follows . . . the MLF is not a given, it’s a blessing.

Reference:

1 Vion, C. et al. (2023). New malic acid producer strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for preserving wine acidity during alcoholic fermentation. Food Microbiology, 112